Welcome to Jenna Repeats History

Hanna Alkaf's author's note in THE WEIGHT OF OUR SKY, my favorite place in the world, and how to write class poems

History repeats itself.

I also repeat history.

I gush about historical fiction novels with my reader friends. I lecture my own children about the history of a place whenever we find ourselves more than ten miles from home. Like every teacher, I repeat myself to students again and again and again.

Just for good measure, I thought I’d capture all this repetition in a newsletter as well. In each weekly issue, you’ll find a history-type book to read and the story behind a place I’ve explored. For you history teachers in the crowd, I’ll include a bit about what I’ve taught lately with copies of my plans and student handouts that you can use with your own students.

So here goes! Welcome to my foray into news-lettering! Since this is my intro newsletter, I’ll start by introducing you to my favorite author’s note, my favorite place in the world, and how I write a class poem to build community in my classroom and learn about my students.

A Book to Read: The Weight Of Our Sky by Hanna Alkaf

I love Hanna Alkaf’s book THE WEIGHT OF OUR SKY for a lot of reasons. The writing is gorgeous, the main character’s mental illness is poignantly portrayed, and the quick pace of the novel is both terrifying and exhilarating. The book is about a piece of history I didn’t know much about - the historic race riots of 1969 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The story unfolds as the May 13th Incident takes place, wherein violence between Malays and Chinese led to the death of hundreds.

But my favorite part of the book is actually the author’s note. I love it so much that I put it in my World History syllabus, as an explanation of why we’ll read fiction to learn about history.

Hanna Alkaf writes:

“I appreciate you because without your eyes, your attention, your willingness to listen, as the memories and voices of those who lived through it begin to fade, this seminal point in our past becomes nothing more than a couple of paragraphs in our textbooks, lines stripped of meaning, made to regurgitate in exams and not to stick in your throat and pierce your heart with the intensity of its horror.”

You’ll not be shocked to learn that the words in my student’s World History textbook do not stick to their throats or pierce their hearts.

Only stories do that.

I try to fill my class with stories.

Luckily, stories are everywhere. Each week, this newsletter will share one such story. Maybe the story will be from a picture book or a snippet from a non-fiction text. Maybe it will be a historical fiction book, a few pages of a comic book, an old newspaper clipping, or even a photograph that will tell a story. I can’t wait to share the things I’ve been lucky to read.

Hopefully, these stories will stick to your throat and pierce your heart, just like Hanna Alkaf’s story did for me.

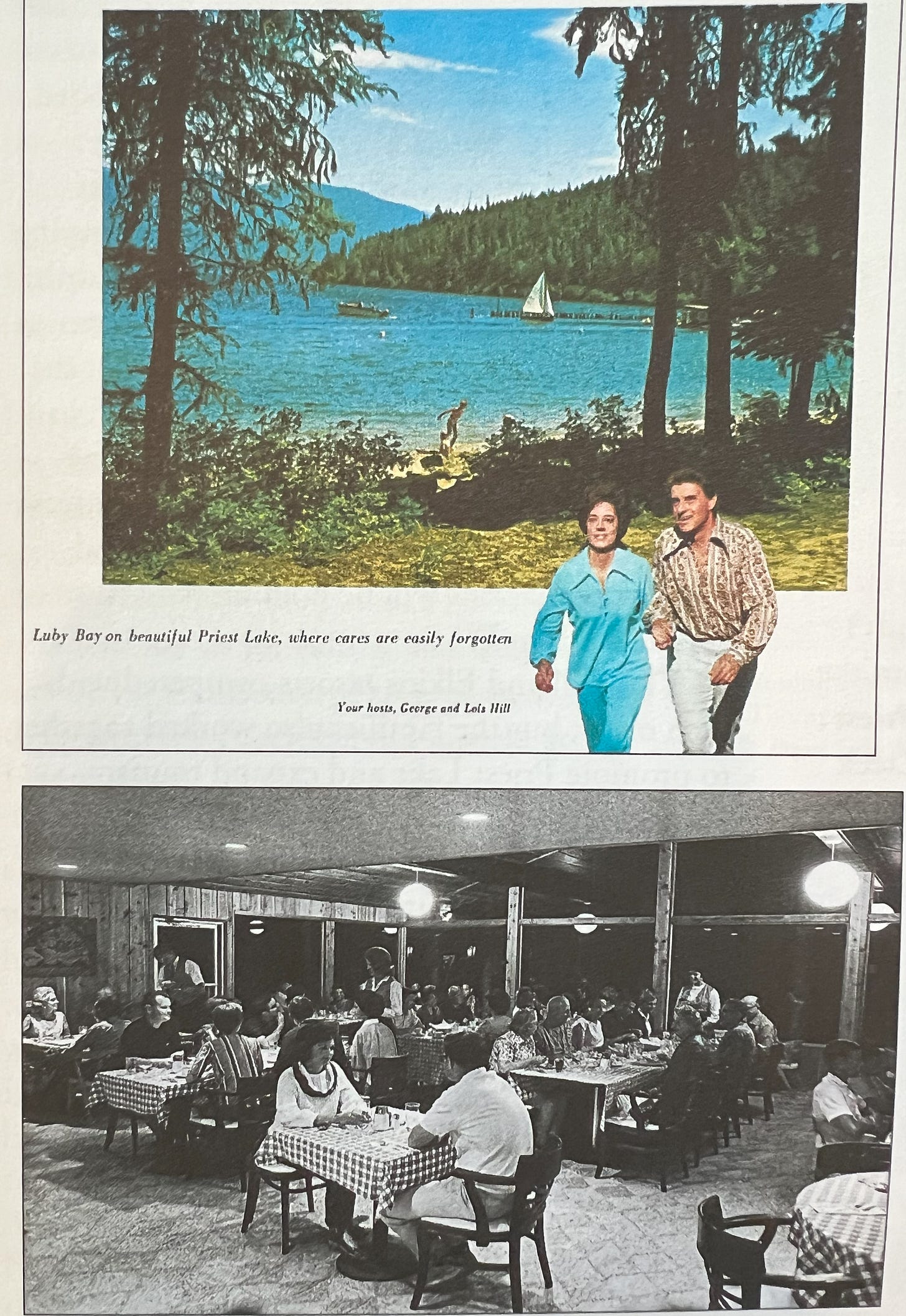

A place to explore: Priest Lake, Idaho

History isn’t only found in stories that have been typed up and preserved. Places have histories and stories too. My favorite place in the world is bound up in my family history. This is, of course, why it’s my favorite place in the world.

My parents first took me to Priest Lake, Idaho when I was three. For the next decade, that yearly pilgrimage to Northern Idaho was the highlight of my year. I still drive across Washington State each summer with my own family, our minivan loaded down with floaties and paddleboard paraphernalia.

But family history at the lake stretches back farther still. My mother vacationed at that same lake for much of her childhood too. When I bought WILD PLACE: A HISTORY OF PRIEST LAKE, IDAHO, my mom recognized old pictures of the resort we always stay at.

My love for this place is all wrapped up in this history. If I’d stumbled upon the lake while I was traveling around the country in my thirties, I surely would have thought “Oh, what a beautiful spot,” and moved on. The smell of pine trees and the sound of waves lapping the shores wouldn’t unlock thirty (okay, okay, forty) years of summertime memories.

Of course, Priest Lake has a longer history still. Since time immemorial, before they were relocated to Montana, Kalispel families crisscrossed the lake in their cedar canoes to fill up on fish, moose, and deer before winter set in. Jesuit priests arrived on the scene in the mid-1800s, giving the lake its name.

My favorite place in the world has withstood many of history’s calamities: mining claims, wildfires, an overzealous timber industry, and a fungus called blister rust that attacks pine trees. Hopefully, that clear blue lake and those wooded mountain peaks will withstand future trials as well - climate change, forest fires, overdevelopment, and the deregulation of National Forest land are all just as scary as that blister rust probably was in the 1950s.

The resilient history of Priest Lake gives me a reason to be hopeful.

A lesson to teach: Writing a class poem

I ask my students about their favorite places in the world too. I ask them about a lot of their favorites, actually. Like many teachers, I give my students a big ‘ol questionnaire on the first day of class, requesting that they fill in all the questions they are comfortable answering.

And then I pour over their answers.

Finally, I turn their favorite places, and favorite foods, and their future career hopes into a class poem. When I read the poem to the class, it’s a funny and rhyming mash-up of all their answers.

After reading the poem, the students laugh and clap, and point out “their” stanza in the poem. On the back, I create a bingo card with all their facts. Then, students mill around, talking to each other as they discover which student goes with which fact.

I tack the poem up on my classroom wall and tell my students that if I ever get mad at the class, I’ll just read the poem, remember that I love them, and won’t feel mad anymore (real talk: this only works about 50% of the time).

For any interested teachers, here is the questionnaire I give my students. Here is a sample poem, and here is the poem template I start with. I kind of MadLibs the thing together, but usually there are always a few stanzas that have to be written from scratch, depending on how students answer questions. Putting the poem together usually takes me about 20-30 minutes per class. I swear it’s worth it.

As always, feel free to reach out if you have trouble accessing the documents, want tips on how to do this in your classroom, or if you find a way to make this work even better in your classroom!